- Home

- A. W. Hammond

The Paris Collaborator Page 2

The Paris Collaborator Read online

Page 2

‘Until we meet again,’ Lucien said. He put the truck into gear and pulled off.

Duchene grabbed hold of the box beside him as they lurched down the street.

They continued up the avenue to the Place d’Italie, following the curve of the large traffic circle past the arrondissement’s town hall. Between its vaulting arches hung Nazi flags, the occupation reinforced to all who passed by. On the streets around them, Parisians walked: the men in linen suits, the women in summer dresses, all three years out of date. But to do anything less than your best was to succumb to the Germans, to the rations, to the malaise of occupation, so hats were embellished, offcuts were repurposed as scarves while leg makeup made bare legs appear as though they wore hosiery. Where the materials were new and the styles fresh, assumptions could be made about the wearers. And with the Americans now on French soil, it took a certain fatalism or wilful ignorance to mark yourself out as a collaborator.

Duchene and Lucien wound their way onto the Boulevard du Montparnasse, arriving at a tree-lined esplanade from which they could just see the lights of the Eiffel Tower. A wide, grassy island ran the length of the street. Here, the last stragglers of picnics were packing up their hampers and blankets to take their celebrations into the well-lit residences that surrounded them. It reminded Duchene of how little and how much had changed – although picnickers had always been common in the centre of esplanades, these were German officers accompanied by Frenchwomen.

Lucien let the car idle while Duchene stepped out on the cobbled street and turned to take the box.

‘What a beauty,’ Lucien said. ‘He didn’t even wake.’

‘He’s a good sleeper. His parents are lucky.’

‘Got to keep moving, find a refrigerator for the butter. I know a pâtissière who’ll pay a strong price, but she won’t be at her shop until first thing tomorrow.’

‘Until tomorrow.’

‘Of course, my friend. Adieu!’

Duchene walked up the stairs to the townhouse opposite. He pressed the buzzer and, after a quick acknowledgement, was let into the foyer. Gripping the box with one arm, he removed his hat and stepped inside. Beneath a large chandelier, a marble mosaic spread across the floor to a curved staircase. It was down this that the woman ran while the man hurried after her.

‘Monsieur Vernier. Madame, I –’

Madame Vernier, barefoot with a house jacket thrown over her nightgown, rushed to the box. ‘He’s all right. Tell me he’s all right.’

‘Jean is fine. He slept the entire way.’ Duchene held out the box while the infant’s mother reached in to retrieve him. On being held close to her breast, he roused and burst into tears.

‘You’ve done an amazing thing, Monsieur Duchene, just amazing,’ Vernier said as he took the box from Duchene’s arms and firmly shook his hand. ‘Tell us what you want, and I’ll do everything in my power to give it to you.’

Behind the tearful mother, padding down the stairs, came the nanny. She tugged at her sleeves, but not before Duchene saw the bruises on her arms. With the infant now in her arms, Madame Vernier turned her back and walked to the opposite side of the foyer.

‘Been difficult times,’ Vernier said as he leant close to Duchene, his breath heavy with liquor. ‘We were going to dismiss the nanny, but she begged and promised to work for us for free.’

Duchene nodded.

‘So, what can I do for you? A new apartment? A car? Nothing is too much for the return of our child.’

‘Thank you, but no. Just what I can carry. Some of that cognac you’ve been drinking, and any cigarettes.’

Vernier turned to the nanny. ‘Sophie, a case of Hennessy and three cartons of Ecksteins for Monsieur Duchene.’ As she hurried upstairs, Vernier leant forward again to Duchene’s ear. ‘Give me their address and I’ll make it two cases.’

Twelve bottles. Worth a fortune on the black market.

‘Sorry, Monsieur. I can’t do that. Those were the terms.’

‘I know, I negotiated them. But come, my friend, these are criminals. My wife has been frantic.’

‘I’m sorry.’

Vernier stiffened and stepped back. ‘Of course. We had an agreement.’

Duchene watched as the Verniers took Jean upstairs. He waited, hat in hand, for another ten minutes before the nanny returned. She gripped the box in both hands, carefully moving down the steps. Her hair came free from her bun, and as soon as she handed the box to Duchene, she neatened the loose strands.

‘Thank you, Sophie,’ he said, then, ‘Reconsider. You don’t need to stay with them.’

She looked up at him, a frown of worry on her face.

‘The Americans will be here soon. You can survive until then. The Verniers will want to flee or stay, and neither is good for you.’

‘That is then. This is now. I cannot leave. Without their protection, you know what they do to people who work for sympathisers? People like us?’

‘Us?’

Her eyes narrowed in confusion. ‘You work for the Verniers too.’

‘I did it for the child.’

‘Then so do I.’

THREE

The Germans had been busy. Duchene passed new fortifications, the fresh hessian of their sandbags a contrast against the dark cobblestones and limestone walls behind them. Commands and watch houses had their windows boarded up and their doorways reinforced. The smell of timber was in the air.

It was no surprise that the streets were empty, more so in recent days than at any other time during the occupation. In the past, the façade had been maintained – this was Paris, after all – and nights were a time for celebration and culture. But now they were quiet. Even in his own neighbourhood, passers-by didn’t raise their eyes to meet his, keeping their hands in their pockets despite the mild weather, moving quickly on to whatever activity had forced them outside.

Duchene turned the key to his apartment building and entered the foyer. He checked his postbox. A habit – it was always empty. He made his way to the first floor, narrow wooden stairs creaking under his tread, seeming to resent the added weight of the box in his arms.

A second key and his apartment door was open. He weaved his way around the stacks of books that lay across a threadbare rug, then cleared a space among the papers on his dining table and was finally free of the cigarettes and cognac. Once he would have carried the case across town with no effort, but his breath left him quicker as he edged closer to fifty. When he looked in the mirror these days, he saw his father’s face, the same receding, greying hairline, the lines cutting across his cheeks, and now the bone structure that had started to show once food shortages came in.

He looked across the room at the slow spread of chaos, the migrating stacks: those books he cherished, those he’d struggled to complete. There were more of them in his bedroom and even a few in his small kitchen. But not in the other bedroom. That remained closed; that remained as it had been a year ago.

He took his handkerchief from his pocket and unwrapped the milk thistle from the farm. Careful to avoid its spines, he lowered it into a sand-filled tank that sat on his crowded windowsill. ‘Ernest,’ he called, peering down into the tank. A cautious head emerged from a black-and-yellow striped shell and swayed from side to side as it sniffed the air. ‘For you. From the forest of Fontainebleau.’

At first, he’d had trouble caring for the creature; its presence had summoned too many bad memories. Even so, to abandon it would have meant to betray his life before the war. This was, after all, a simple tortoise, and the memories were his burden to overcome.

Eventually, Ernest crept up on its meal and started to eat.

‘Enjoy,’ Duchene said as he stroked its neck.

His duty done, he navigated the drifting library and made his way to the kitchen. In the breadbox was the heel of a stale loaf; toasted, it might suffice. Perhaps food w

ould have been a better payment. In the larder was the last of his butter, two potatoes, some sardines and a can of compressed meat. He strongly suspected the wine bottle on the cupboard beside him was empty – double-checking it wouldn’t make it full again.

Duchene rolled up his sleeves and began to wash his hands.

There was a knock at the apartment door.

‘I thought I’d heard you come in,’ Camille said as she stood in the doorway.

‘I’ve been out.’

A wry smile crossed her lips. ‘This much is clear by your standing in front of me.’

‘Are you going to come in?’

‘I’d fear I’d topple something. I wanted to see if you’ve had dinner. I have made a gratin, and you’re welcome to share it.’

‘I don’t have much I could exchange. My cupboard is empty. Unless …’ He returned to the dining table, lifted a bottle of cognac from the box and held it towards Camille.

She crossed the room, slipping easily between the stacks of books. Unlike Duchene, she had always been slim, keeping up her callisthenics. There couldn’t have been more than a year or two between them, but when he looked at her toned arms and calves, and the freckles on her face, it was as though time was passing more slowly for her.

When she noticed him watching her, he turned his attention to the bottle in his hand. ‘For after?’

She took it from him. ‘Where did you find them? Actually, don’t tell me, I don’t want to know. You should keep it. Sell it.’

‘Let’s enjoy it instead.’

‘Food, company, drink. Sounds good.’

He locked up, and they crossed the hallway and walked through Camille’s open door. No matter the many hours he spent in her apartment, he was always amused by its familiarity and difference. It mirrored his, with the bedrooms at the same end, the kitchen and bathroom at the other. The cornices and mouldings, although in better repair than his, were the same, the inbuilt cupboards and kitchen furnishings identical. However, her decor, unlike his, would have met with the architect’s approval: the statues, vases, and large framed photographs on the wall were as current as possible in a time of war.

On a walnut coffee table between two angular club chairs, the meal still steamed. It smelt of butter, toasted breadcrumbs and cauliflower. Beside the gratin was half a fresh baguette.

‘It’s just a Dijon roux,’ Camille said. ‘No cheese, I’m afraid.’

‘It’s wonderful.’

‘Let’s get it done, then. I’m keen on that cognac.’

He nodded and held the plates as she served them from the dish. A cooked meal made from fresh food. The gravity of the moment wasn’t beyond them, and she had brought out her best dinner service to mark the occasion.

They sat in the club chairs, a fork in one hand and plate in the other. Camille paused and examined her meal, and Duchene watched her in silence. It was as though she was trying to discern something, read the signs. ‘Please, start,’ she said as she gently shook her head.

He did. But just a small mouthful, so he could ask, ‘What’s troubling you?’

‘This meal. Every meal. Do you know what I mean?’

‘Yes.’

‘Do you remember when they first arrived?’

‘Of course.’

‘I remember this officer. He’d seen me playing in a club, learnt that I was a piano teacher, wanted lessons. He’d been learning back in Germany, before the war, and wanted to keep up. I couldn’t understand it – this enemy, wanting to make art, to improve himself through creating beauty …’

‘A contradiction.’

‘It was. But that’s not what troubled me the most.’

‘No?’

‘No. He wanted to pay for his lessons, my full fee, when he could have just forced me to teach him for nothing. To have him want to pay me … It legitimised him. For him it was the polite thing to do, but for me it was frightening. He was here to stay, to live in Paris, to pay for our services. To become one of us – no, worse, we were to become one of them.’

‘What did he want to learn? Wagner?’

Camille laughed. ‘Not so clichéd. Tchaikovsky. Can you imagine? But enough of that.’ She shook her head, her smile lifting the lines on her face and guiding his gaze to her eyes that gave him their full attention. As Duchene had aged, he had felt slow and sullen, his advancing years like a rot setting into an old stump. Camille seemed to cherish her moments and rise above the malaise of the occupation.

‘This is delicious,’ he said.

‘It’s nothing. Really.’

He tried to take his time, but the roux was flawless, and in no time he had eaten it all. He waited in silence for Camille to finish. She nodded to him, and at this signal he collected two glasses from the sideboard.

‘I saw Marienne today,’ Camille said.

‘She was well?’

‘Yes. She’s invited me to dinner.’

‘You can’t go.’

‘Of course I can.’

Duchene uncorked the cognac, poured generously and handed her a glass.

‘She asked after you,’ Camille said. ‘You should talk to her. Make more of an effort.’

‘Cheers,’ he said and held out his glass.

She chimed and brought the cognac to her nose before taking a sip. ‘And what about Marienne?’

‘All right, yes. I’ll make more effort.’

‘Your daughter still needs you. No matter how angry she gets.’

‘I really don’t want to talk about that.’

‘What shall we talk about then? Your turtle?’

Duchene sighed. ‘When they’re little, you’re filled with joy at even the simplest things they do, like reading a word. I think because it gives you a sense of their opportunity, of the life that lies open to them. But when they get older and make disappointing choices, so much potential seems lost.’

‘Well. She’s in love.’

‘So you agree with her decision, then?’

‘It’s not really for me to say.’

‘Why not?’ he said. ‘You’re the one she confided in as she grew into a woman. You might as well be her mother. In many ways …’

Camille shook her head. ‘I think it’s a bad decision, short-sighted. Look at the world we live in. The Americans are coming. What is to be gained from it?’

‘She’s stubborn.’ Duchene poured another glass. ‘Like her mother.’

‘Of course she’s stubborn. She’s like you.’

***

The yellow glow from the street lamp cascaded through the venetians. It was just enough light to see the half-empty bottle of cognac. Duchene poured another glass. Soon it would be morning, and he would have to face another day.

The turtle moved in its tank, oblivious to its own significance.

The bomb had landed close to the school. One moment he was teaching English prepositions, a moment later the room shattered.

The bomb is in front of the building.

The force of the explosion passed over him and threw him to the floor. With each breath, his ribs tore pain across his chest. Dust filled his lungs, choking him, clogging his mouth with grit and blood. His ears rang, the pain like the stab of a knitting needle.

The room is under rubble.

As he pulled himself free, the sun broke through the plumes of dust and smoke. Among the debris was a section of wall. Sitting against it, glinting in the light, was a glass reptile tank. It was undamaged. It was the only thing that remained. A field of rubble lay before him, and small, unmoving bodies lay beneath it. The roof had fallen. The space that had once contained desks, bags and bookshelves was now littered with broken wood and shattered tiles.

The children are among the dead.

Tuesday, 15 August 1944

FOUR

A mist h

ad risen from the Seine and refused to fade in the morning light. Autumn had announced its intention to return to the city with a grey chill. When Duchene dragged himself from his apartment, the last tendrils of the night flowed around Parisian and German alike. He wore his winter coat and carried a worn valet bag.

From his apartment in Quartier Saint-Ambroise he made his way to the river and followed it to the Tour Saint-Jacques; he passed men and women starting their working week. A captured city had to function to prove the legitimacy of its occupiers. To illustrate the point, a large group of soldiers supervised council workers as they tore down posters calling for a general strike. Someone had stuck the notices around the square with flour paste, a sign that not only had the night’s curfew been broken, but also that civil unrest was looming. This explained the speed at which people were moving, their heads down, eyes averted. Even the soldiers shifted on their uneasy feet while this challenge to their authority remained.

At the café tables on the square, senior officers sat drinking coffee and smoking. In this sea of grey uniforms was Lucien. He was sharing cigarettes with a young lieutenant and waved to Duchene as he approached.

Lucien stood up, gripped Duchene’s arms and kissed his cheeks. ‘You look like hell, my friend.’ He turned back to the officer and spoke in German. ‘Oberleutnant Ritter, this is Monsieur Duchene.’

Duchene nodded back. ‘Oberleutnant.’

The officer reached out a hand, and Duchene shook it.

‘The Oberleutnant has the day off duty in the city. I’ve recommended he visit the Sphinx, but that’s for tonight. Since he’s been here, he’s seen the Louvre, Sainte-Chapelle and Notre Dame. Anything else to recommend?’

Duchene paused. ‘Saint-Séverin.’

‘Of course. Latin Quarter. A good visit – beautiful mosaics. Get your fill of piety before you head out for a night of sin.’

The lieutenant laughed. ‘Got to have a balance.’

‘That’s right. In Paris we do all things in moderation. But we do all things, if you take my meaning.’ Lucien clapped his hands together. ‘Well, we must go.’

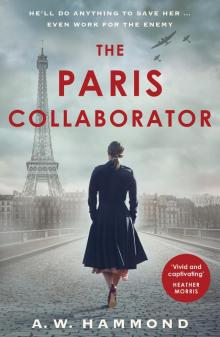

The Paris Collaborator

The Paris Collaborator